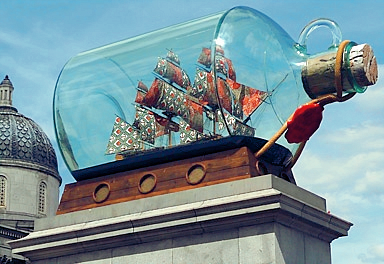

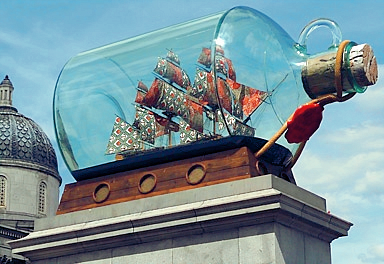

Nelson's Ship in a Bottle

Yinka Shonibare, MBE

b. 1962, London

'Nelson's Ship in a Bottle' is a sculpture of Nelson's flagship 'HMS Victory'.

The sculpture considers the relationship between the birth of the British Empire, made possible in part by Nelson's victory at the Battle of Trafalgar, and multiculturalism in Britain today.

"For me it's a celebration of London's immense ethnic wealth,

giving expression to and honouring the many cultures and ethnicties that are still breathing precious wind into the sails of the United Kingdom."

Yinka Sonibare, MBE. The sculpture is 3.25 metres high and 5 metres long and weighs 4 tons

Yinka Shonibare isn't nervous about how the critics will respond to his commission for Trafalgar Square's famously empty fourth plinth.

What would be the point? The ship is in the bottle: there's no going

back now. And how, exactly, did it get into the bottle? He grins,

gleefully. "I'm not saying." Was it perhaps a hinged, fold-up vessel,

one he could unfurl inside the bottle inside using those mechanical arms

that park keepers use to pick up autumn leaves? He shakes his head. Or

maybe the bottle's neck is sufficiently wide that he was able to slither

in and out at will? "I've told you: I can't say. It's a secret." All he

will reveal is that the bottle itself is not made entirely of glass

(it's some kind of polymer blend); that it was manufactured, not in

Britain, but elsewhere in Europe; and that a wax seal on its side will

read: "YSMBE" (his initials, followed by the honour he received from the

Queen in 2005). Oh, yes, and there will be a row of Union flags along

its prow.

From the moment the Fourth Plinth Commissioning Group

wrote to him three years ago, asking him please to submit a proposal,

Shonibare knew in his gut what he wanted to stick on London's

highest-profile site for sculpture. "It's a huge honour to do something

for Trafalgar Square," he says. "And it seemed obvious to do a work that

was connected to the square in some way. I'm surprised no one has done

that before. I wanted to do a serious thing for a serious space, but I

also wanted it to be exciting, magical, and playful." His big idea was

Nelson's Ship in a Bottle,

a large-scale model of Horatio Nelson's ship, HMS Victory, from which

he commanded the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. The twist in the tail,

however, is that this ship's sails would be made of Dutch wax, the

brightly coloured African fabric that is Shonibare's trademark.

"Nelson's victory freed up the seas for the British, and that led, in

turn, to the building of the British Empire. But in a way, his victory

also created the London we know today: an exciting, diverse,

multicultural city." So his work is intended to be celebratory rather

than critical? "Both. I want to make people think. I love London. I

don't know any city like it. It has a unique vibe. Maybe this is just a

monument to live, and let live."

Shonibare, an unexpectedly

willowy man in a spiffing powder-blue jacket, is used to attention. His

work has been shown in every major gallery in London (not to mention the

Louvre in Paris, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York), and in

2004, he was shortlisted for the Turner prize. But still, the plinth

commission is different. "The Turner was quite full-on. I'm a winner,

not a loser, and I hated not winning. It irritated me, it annoyed me.

But you move on. I was already collected, I was already making money;

the Turner didn't change anything. But then came the plinth, and that

was a huge compensation, and it already feels bigger than anything else.

The work will be there for 18 months. So many people will see it."

Where is it now? We are in Shonibare's studio in London Fields, Hackney,

the smaller of two premises in which he works, and all I can see is the

maquette he made when he submitted his original proposal. "It's

somewhere else," he says. His face is a picture of innocence, lightly

tinged with mischief.

Although he works in different media –

painting, sculpture, film and photography – Shonibare's work has

followed an unusually clear trajectory since he left Goldsmiths in 1991.

As a student, he had been busy making work about perestroika until, one

day, a tutor asked him why he didn't think about African art instead.

Intrigued by the idea that he should, as a person with a Nigerian

background, be expected to make only "African art", Shonibare began

considering stereotypes and the issue of "authenticity". His research

took him first to the Museum of Mankind and then to Brixton market. He

discovered that the exuberant batik that goes by the name of Dutch wax

was not, in fact, African; originally, it was Indonesian. Dutch

colonialists, hoping to make a profit by selling it, had set out to

manufacture the cloth commercially in the Netherlands. When their

venture failed, they palmed off the surplus on west African markets,

where it somehow became, over time, a kind of national costume for

millions of Africans: a statement, in the 20th century, of their

post-colonial independence.

Ever since, Shonibare has used the

fabric in his art, with dizzying results. Initially, he began mocking up

entire Victorian rooms, except their chaises longues were covered, not

in velvet and silk chintz, but in Dutch wax. Emboldened by the success

of these experiments, he then began using the cloth in his responses to

iconic 18th-century paintings, such as Thomas Gainsborough's

Mr and Mrs Andrews, and Henry Raeburn's

Reverend Robert Walker Skating on Duddingston Loch. In Shonibare's

Mr and Mrs Andrews Without Their Heads (1998), and in

Reverend on Ice

(2005), headless life-sized mannequins recreate the poses of the

subjects of the original paintings, only their clothes are fashioned

from Dutch wax. These installations and sculptures are provocative, of

course, but they are funny, too. "Yes,

Reverend on Ice is

funny," says Shonibare. "I wouldn't have made it otherwise. It's a

parody: it's two fingers to the establishment. I do think Raeburn's

painting is beautiful, but perhaps in a way that other people don't. I

see a dark history behind its opulence. I think: who had to be enslaved

in order for you to be able to afford a portrait painter? So it's

gallows humour, too."

His work, he believes, reflects his

ambivalent attitude towards the establishment, acknowledging the

perversity that, sometimes, a person can find something both abhorrent

and deeply attractive. In a series of photographs called

Diary of a Victorian Dandy

(1998), he presents himself as the frock-coat-wearing hero, playing

billiards, lying abed attended by half a dozen servants, or posturing

before mustachioed types in his library. "When I think of that era, I

think about domination and repression. But I also admire things about

it. I enjoyed dressing up in those clothes. I don't deny that. It's the

same with my MBE: I love it."

Is he joking? "Honestly! For one

thing, there is no British Empire. It's finished." There's still

Gibraltar, I say. He laughs. "Also, I have a whole list of

contradictions. Just because I'm a black artist, I don't want to have to

stand on a soap box all the time. I admire the Queen; I love the royal

family. A lot of people will think I don't really mean that. But I do.

The establishment is fascinating – the idea that, thanks to an accident

of birth, your whole life is laid out for you. The only thing is that I

don't know my place. I'm not at all a good subject in that sense."

Shonibare

was born in London in 1962, but moved with his family back to Lagos

when he was three. He comes from a wealthy, middle-class background: his

father was a successful lawyer; his brothers are a surgeon and a

banker, his sister is a dentist. It would be something of an

understatement to say that his parents were appalled when he started

talking about wanting to be an artist. "I was a freak! Success is so

important in Nigeria. When you're some young, tramp artist, you're

considered a drop-out. During the early part of my career, I was always

phoning home for money. My father would say: 'When are you going to grow

up?' I was on something like £5,000 a year. I wanted a deposit so I

could buy a house. I got the deposit, but, oh my goodness, the lecture!"

These days, his family's attitude is rather different. "Too bad my

father didn't live to see me get the MBE. He would have loved that –

though it's ironic that I got it by being subversive, by being the

opposite of what he wanted me to be. But [before he died] I was invited

to Windsor Castle for a party, and he was so excited. I heard him on the

phone saying: 'Yeah, I encouraged him to go to Goldsmiths.'"

After

school in Lagos, there followed a stint at a British boarding school

("a Nigerian middle-class thing; I hated it – it was cold, and all the

food was boiled, no spices") after which he enrolled at the Wimbledon

School of Art. Two weeks later, however, he fell ill; a virus in his

spine left him completely paralysed. "It took me three years to recover.

I had to learn to walk again. At first, my mum looked after me. Then I

moved to a rehab centre. It was extremely isolating. But as soon as I

was back at art school [he went to Byam Shaw and then, for his MA,

Goldsmiths, where his contemporaries included the Wilson twins and

Matthew Collings] I started winning awards. That encouraged me. I

thought: OK, I have a disability, but people can judge me by my work.

It's about what I can do. In that sense, art has been like a life

support system for me." Today, he walks with a stick, and his body is

slightly curved. But he suffers no pain. "I make sure I keep mobile, I

don't let myself get too stiff. You're only noticing because you're

meeting me for the first time."

After Goldsmith's, with its

notoriously critical tutors – "it's that military thing; they destroy

you completely and then they rebuild you" – Shonibare found himself

frozen for about two years, "unable to produce anything". In 1997,

however, his work was included in Charles Saatchi's infamous

Sensation

show at the Royal Academy. After this, there was no stopping him. "I've

been lucky. Audience response has always been good, and every time I've

done a show, it has led to invitations to do three more." What role, if

any, does he think his colour has played in his career? "I'd be lying

if I said I had suffered discrimination, though I'm not naive enough to

think it doesn't exist. But in any case, I love a challenge, so if you

don't think much of me, I will do things to make you consider me more

highly." What about positive discrimination? "People do that only once.

They invite you, and if you produce crap they won't invite you again,

full stop." On a blackboard, his schedule for the next 12 months is

already chalked up. It includes shows in Monaco and Israel, in Spain and

in Australia. He could not, he says, be busier if he tried.

I

wonder if he finds conversations about multiculturalism tiresome, for

all that his work invites them. I wouldn't blame him if he did.

Shonibare shrugs. "Culture has a role to play. In a diverse society

people have to find a way of being together, and that can only come from

understanding other cultures. Otherwise, you're just fighting for

space. But I'm from London, now. I've been here for 30 years. In Lagos, I

would feel like a foreigner. The city has had such an impact on my

work. If I'd lived somewhere else, I'm certain that my career would have

evolved very differently. And I love it. I love what you could call

'vindaloo Britishness'. It's a mixed-up thing. You hear it in British

music, and you taste it in British food. This purity notion is nonsense,

and I cherish that." His trademark Dutch wax is, he says, a metaphor

for interdependence and thus, perhaps, a metaphor for city life as well.

We all pinch from one another. We take what we like, and in doing so,

we are, whether we like it or not, joined together in one great and

vibrant web.

Figure 1

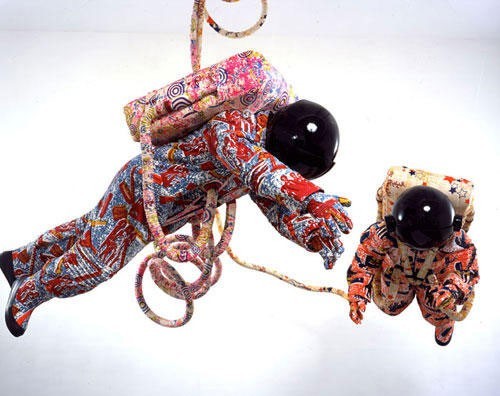

Figure 2

Figure 3

Work Cited: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nelson%27s_Ship_in_a_Bottle_by_Yinka_Shonibare.jpg

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2010/may/16/yinka-shonibare-fourth-plinth-trafalgar

figure 1: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nelson%27s_Ship_in_a_Bottle_by_Yinka_Shonibare.jpg

figure 2: http://adventures-of-the-blackgang.tumblr.com/post/1045056488/yinka-shonibare-victory-bottle

Figure 1

Figure 1